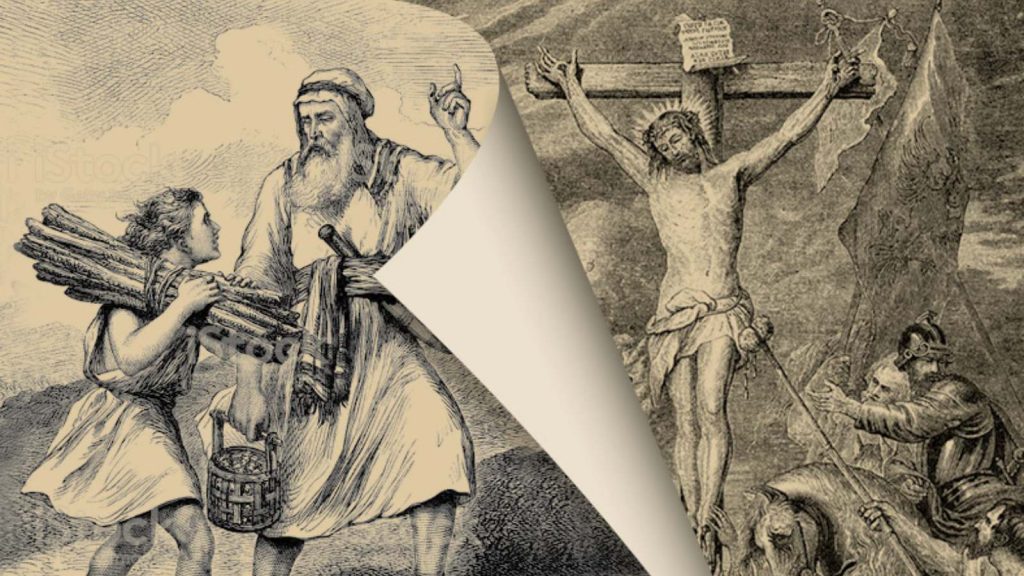

Ethan’s Dad: Particularly since we recently celebrated Easter, I want to pick up a thread of what Ethan’s mom talked about in her last post. If you are a Christian, there can be a palpable tension about the subject of death. We are taught from early on in our Christian walk that the existence of death is a consequence of sin that began with Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. It signifies the seriousness of the separation between God and humanity sin produces. Yet, we are also taught that death is not the true end of the story of life: that yes, Jesus came and died, but also that He rose from the grave, and because He conquered death, we will be reunited with God — and with everyone who has died believing upon Jesus — in the age to come. Thus, for the Christian, death is simultaneously understood as the ultimate enemy of God’s original design for creation and also as an obstacle that Jesus has overcome, and so it should not be feared. At times, you will even read or hear Christians — wrongly I think — attempt to meld those two ideas into a lesson that death is really just a natural part of life.

The theme of Ash Wednesday is sometimes twisted into this idea that death is a natural part of life. Ash Wednesday asks us to ponder the fact that we are dust. From dust we came and to dust we shall return. (Genesis 3:19). The Psalmist prays for God to teach us to number our days. (Psalm 90:12). Paul reminds us that we are the clay and God is the potter. (Romans 9:19-21). So, this idea runs throughout Scripture. On Ash Wednesday, the fact that we are dust is said solemnly — with a sense that we prefer not to think about death, that we avoid the fragility of life, that we distract ourselves from reality.

But what about those of us for whom death is all too real? Each week, I take time to sit at Ethan’s grave, and death is all around me. I carry Ethan’s death with me every day. I do not have to will myself to ponder the fleeting nature of life here on earth because I helplessly watched it slip away from a two-month old. So, for me, Ash Wednesday does not conjure anything that I strive to avoid. And saying that we just need to accept that death is part of life feels like asking me to be okay with Ethan’s death. But I cannot do that. No matter how much I contemplate the inevitability of death, or the lack of control over when it comes, or the fact that it affects everyone, it does not quell this knot within me that screams that this is wrong, that it is not the way it should be, that a theft has occurred which cannot be restored.

Moreover, the idea that we are “just dust” does not tell the whole story of who we are. Scientists will tell you that our bodies are made primarily of carbon and water. But in the Bible, dust and clay are used as metaphors to give us pictures of our relationship with God, not as scientific observations. The Bible is full of exhortations about our souls, the spiritual part of our being.

- Deuteronomy 6:5: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength.”

- Psalm 23:3: “He refreshes my soul.”

- Psalm 35:9: “Then my soul will rejoice in the Lord and delight in his salvation.”

- Psalm 84:2: “My soul yearns, even faints, for the courts of the Lord; my heart and my flesh cry out for the living God.”

- Matthew 10:28 (Jesus speaking): “Do not be afraid of those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul. Rather, be afraid of the One who can destroy both soul and body in hell.”

- Hebrews 6:19: “We have this hope [of salvation by Jesus] as an anchor for the soul, firm and secure.”

- 1 Peter 1:9: “For you are receiving the end result of your faith, the salvation of your souls.”

Thus, the Bible teaches that when our bodies die, our souls do not. Furthermore, the Bible tells us that the birth of sin into the world did not just result in physical death; it caused spiritual separation between God and humanity. In fact, this is deemed to be the more serious aspect of sin’s consequences. And when Jesus died on the Cross, He did not just take our deserving physical punishment for sin; He also endured spiritual separation from God. This is why He says on the Cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46).

That takes us forward to Easter because when Jesus rose from the grave, He unequivocally conquered physical death, but He also restored the spiritual gap between God and humanity. The central message of Christianity is that “God so loved the world” — that is, humanity, we physical and spiritual beings who bear His image — “that he gave His one and only Son, that whoever believes in Him shall not perish but have eternal life.” (John 3:16). That eternal life is both physical and spiritual. Revelation ends with the resounding proclamation that one day Jesus “will wipe every tear from our eyes. There will be no more death, or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.” (Revelation 21:4). Paul also tells us that when “the end comes, [Jesus] will hand over the kingdom to God the Father after he has destroyed all dominion, authority and power. For Jesus must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. The last enemy to be destroyed is death.” (1 Corinthians 15:24-26).

So, death is the enemy that Jesus has overcome. Yet, for us, physical death is still here. It lingers, and it hurts. And that accounts for the tension I mentioned at the beginning of this post. The tension exists because, if you are a Christian, you live in the “in between”: the “already but not yet” context of knowing and believing that Jesus came, died, and rose again to save us from sin and death, but that He has not yet come again to place all things under His feet.

We are not unique in living in an “in between” age. The Israelites lived for hundreds of years in between the promise of a Messiah to come and His arrival. In fact, if you date it from the first implicit reference to Jesus in Genesis 3:15, they lived for thousands of years before His coming. Micah 7:7 echoes the sentiment: “I will watch in hope for the Lord. I will wait for the God of my salvation. My God will hear me.” Certainly, our “in between” age is better than theirs because, by the grace of God, we know who the Messiah is and what He has done, and even what He will do at the appointed time. But it is still not an easy time because there is pain, separation, and loss that exist in abundance in this world.

When Adam and Eve sinned in the Garden, could God have separated them (and by extension us) from Himself spiritually without imposing physical death as a part of the equation? In the sense that God can do anything, I suppose this was possible. But as I said earlier, the Bible tells us that to be human means that we have a dual nature: physical and spiritual. This is why, in order for God to experience everything as we do, He had to become fully human; God is spirit (John 4:24), but through Jesus He also became flesh (John 1:14). For us, committing sin means spiritual separation from God, but it also ultimately entails physical death. So, one reason Jesus had to physically die on the Cross and not “just” experience spiritual separation from God the Father was because the consequences of sin for human beings involves experiencing both, and then His saving humanity required reuniting the physical and the spiritual for eternity though a physical resurrection.

In other words, Jesus died not only to restore the communion of our spirits with the Lord, but also to redeem our bodies. To put it simply, matter matters. Sometimes I think we Christians lose sight of this fact because Jesus talked so often about how His “kingdom is not of this world.” (John 18:36). Christians get caught up in thinking that Jesus meant that His kingdom is just spiritual rather than physical, but it is not quite that simple. Jesus is the King of both heaven and earth.

“For the Lord is the great God, the great King above all gods. In his hand are the depths of the earth, and the mountain peaks belong to him. The sea is his, for he made it, and his hands formed the dry land.”

(Psalm 95:3-5). God’s creation of this world and of us as dual-nature beings, Jesus’s incarnation, His physical death and His resurrection — they all resoundingly demonstrate that our physical world, this flesh-and-blood life, is important. This is precisely why death is a profound event: the cessation of physical life — especially the deaths of the His creations made in His image — is no trifling matter to God. It is not just “the natural way of things”; it is a blight that Jesus came to reverse.

So, death is wrong, it is the enemy, because our lives are sacred and precious. But there is this part of me that keeps wondering if there is some other kind of purpose to death than just being a foil — the desolation that we praise Jesus for overcoming — while we Christians live this “in between,” which, in the personal sense, means we have been spiritually reborn (John 3:3), while we await the physical resurrection. During this “in between” we live with the loss of those who go before us and face our own physical deaths. Why?

Is it, at least in part, that it serves as a way for us to measure what is to come? Romans 8:18 reminds us that we should “consider the sufferings of the present time as not worthy to be compared to the glory which shall be revealed to us.” In a sense, that is asking us to do a comparison of our lives in the present physical world and our lives in the future in God’s restored kingdom. Are we only capable of measuring the bounty of eternity by facing, possessing, and living with a temporal ending to our own lives and the lives of those we love? Isaiah 51:6 commands us to:

“Lift up our eyes to the heavens, look at the earth beneath; the heavens will vanish like smoke, the earth will wear out like a garment and its inhabitants die like flies. But the Lord’s salvation will last forever, the Lord’s righteousness will never fail.”

Will we only grasp the permanence of God’s saving grace through Jesus after having lived, loved, and lost in this time of mortality? We would only be able to do this because of the unique creations God made us to be. That is, because an integral part of us is physical, we experience the agony of death — both those around us and ourselves — but because our souls are eternal, we will be able to remember our physical lives, the loss that death brought, and how Jesus rescued us from that despair. This is perhaps part of what Peter meant when he said that “even angels long to look into these things” that pertain to the salvation of our souls,” because they do not experience this dual life. (1 Peter 1:12).

The loss of Ethan honestly would be soul crushing without the hope of the resurrection. Living with this loss forces me to surrender what is beyond my control to God in a way that nothing else is probably capable of doing. So, it just may be that through experiencing the devastation of death that we grow to understand that life is only truly lived through and for our Maker.