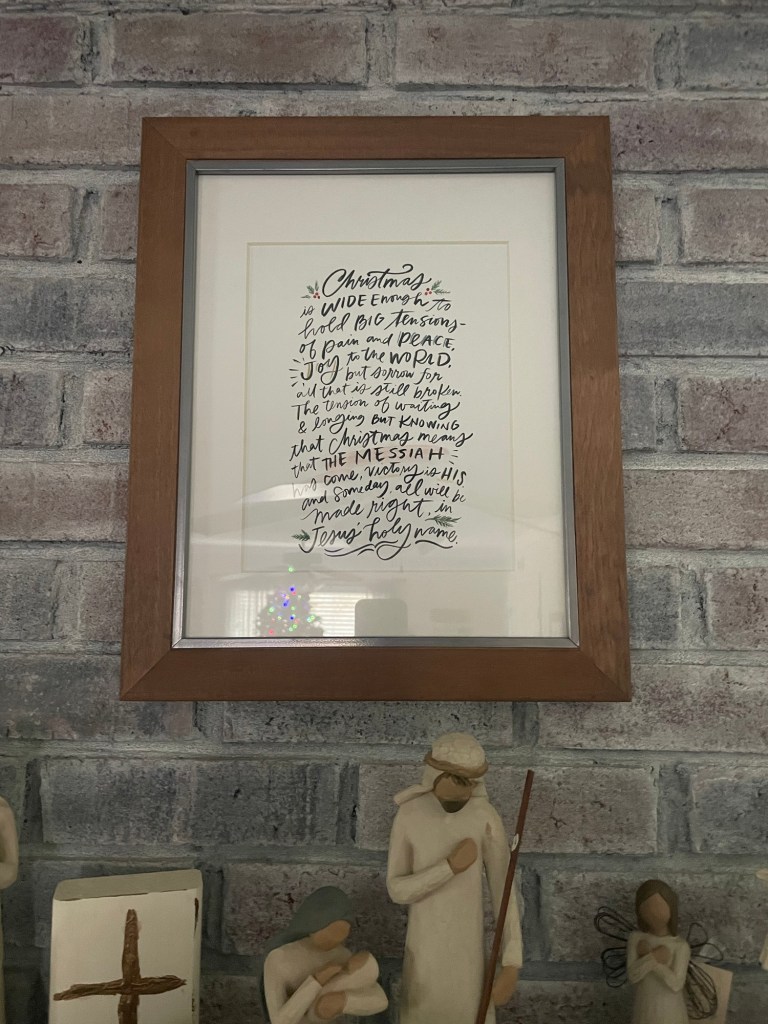

Ethan’s Mom: A couple of years ago, I found a hand-lettered print that we now display every Christmas. It reads:

Christmas is wide enough to hold big tensions – of pain and peace, joy to the world but sorrow for all that is still broken. The tension of waiting & longing but knowing that Christmas means that the Messiah has come, victory is His, and someday all will be made right, in Jesus’ holy name.

I need that reminder every year. I remember sitting in a grief counselor’s office in the fall of 2017 asking if I would ever enjoy Christmas again. I used to love Christmas, I said, but I want to skip the whole thing this year. My capacity to hold joy and sorrow has grown significantly over the last six years, but I still struggle to hold all the joy of Christmas with the pain of missing Ethan. Although we have developed traditions which keep his memory alive in our celebrations, we have never spent a Christmas with our entire family. The closest we have been was in 2016 when I was 34 weeks pregnant with the twins.

This year, the words from that print seem especially significant. The Wednesday after Thanksgiving, a teenager in our church died unexpectedly. The following Sunday was both the first week of Advent and his memorial service. I shed many tears between those two days. I cried for the abrupt end of his life, for his parents and siblings, and for his friends at church and their families.

I also cried for the abrupt end of Ethan’s life, for my family, and for me. There are several details that differ between our stories. For instance, Ethan’s siblings were much younger and grieved in a very different way than teenaged siblings would after sixteen years of life together. But you don’t have to look too hard for the similarities. One night, we went to bed without any indication that our sons would not be alive the next morning. We both had taken last group pictures of our children not knowing we would never have a complete family photo again. We were both left with a million questions, most of which have no answer. All of these thoughts swept me back to March 2017 in a way that I had not experienced in a long time.

Like many people who love this family and wanted to support them in the shocking aftermath of that day, I wanted to do something. It turns out, our immediate role was not to make a casserole or send flowers, it was to light a candle.

Our family had been asked to light the first candle of Advent the day before anyone had any notion that the week would take such a tragic turn. The litugrical calendar specifies a theme for each week of Advent, and the first week is hope. Sometime late in the week, I realized how important it would be to light that particular candle on the very day that held not only the first worship services since this teenager passed away but also his memorial service later that afternoon.

It may not seem like a lot to light a small candle in the face of so much darkness; I confess that I initially thought it might not even matter to anyone except for me. But then I remembered an exceprt from one of my favorite read aloud series, “The Green Ember.” The series follows a group of rabbits as they fight for freedom from their birds of prey captors, and the four books are full of examples of true courage and hope. In book three, after the wizened captain explains to the young hero that his job in the upcoming rebellion is not to fight but to unfurl a banner over the battle raging below, the young rabbit denies his instinct to charge into the battle.

How could he help them? He knew he could help them most by shifting the battle in any small way…Then he remembered Helmer’s words, ‘Symbols matter, more than you might imagine.’ Picket’s heart was pumping fast, and he wanted badly to join the battle. But he banked and swept over the center of the skirmish…He waved the torn banner back and forth. “For the Mended Wood!” he cried. He heard an answering shout over the din of war and felt inside the fire of the good fight. He knew that all around, from the desperate fighters in the square to the hundreds rushing into First Warren through the west wall breach, the sight of this renowned warrior waving the true king’s banner atop this desecration of a statue was one to set the faintest heart on fire.

Ember Rising by SD Smith

I do not claim to be a “renowned warrior” but I am a veteran fighter in the ongoing battle against the darkness of dispair. After six Christmases of “holding the tension between joy to the world and sorrow for all that is still broken,” I felt that our family was uniquely empowered to light the candle of hope that morning. It felt like a mission. The hope candle is the first candle, lit before the candles of peace, joy, and love can shine. It’s the first flicker of light, breaking the darkness. It paves the way toward the full illumination of the Advent wreath with its Christ candle glowing in the center on Christmas Day.

I pray that tiny flame shifted the battle in any small way for our church family that morning. I have heard from a few people who reached out to say that the meaning was not lost on them. In some mysterious way, that candle also shined a little tiny bit of redemption on our story. If you have read this blog at all, you know this has been the hardest thing Ethan’s dad and I have experienced, individually and together. But we are still here, standing, fighting for the light, holding on to hope through another Christmas season without Ethan.

One week later, we gathered for our church Christmas musical, a wonderful concert with an intergenerational choir, orchestra, and scenes from the nativity. It was a truly joyful time, but not without its own moments of sorrow. The juxtaposition between the two weeks was apparent – one very sad day with a spark of hope and one very joyful day with a bittersweet note in the air. We could gather for both, knowing that Christmas is big enough to hold it all.

On this Christmas night, whether you find yourself holding on fiercely to a small flickering flame of hope or in the warm glow of a joyful celebration or somewhere in between, I pray that you know “that the Messiah has come, victory is His, and someday all will be made right, in Jesus’ holy name.” Amen.

By: We the Kingdom

Light of the world, treasure of Heaven

Brilliant like the stars, in the wintery sky

Joy of the Father, reach through the darkness

Shine across the earth, send the shadows to flight

Light of the world, from the beginning

The tragedies of time, were no match for Your love

From great heights of glory, You saw my story

God, You entered in, and became one of us

Sing hallelujah, sing hallelujah

Sing hallelujah for the things He has done

Come and adore Him, bow down before Him

Sing hallelujah to the light of the world

Light of the world, crown in a manger

Born for the Cross, to suffer, to save

High King of Heaven, death is the poorer

We are the richer, by the price that He paid

Sing hallelujah, sing hallelujah

Sing hallelujah for the things He has done

Come and adore Him, bow down before Him

Sing hallelujah to the light of the world

Light of the world, soon will be coming

With fire in His eyes, He will ransom His own

Through clouds He will lead us, straight into glory

And there He shall reign, forevermore

Sing hallelujah, sing hallelujah

Sing hallelujah for the things He has done

Come and adore Him, bow down before Him

Sing hallelujah to the light of the world

The light of the world

Ethan’s Dad: My wife has mentioned in this space before that sitting in church can be a trying experience for us. We never know when a song, a prayer, or a statement made in Sunday School banter might open the floodgates of sadness that reside within us from losing Ethan. Of course, this is also true in everyday encounters, but we have found that the likelihood of it occurring is magnified in church because mortality and miracles are topics of discussion in church much more often than in everyday life.

Ethan’s Dad: My wife has mentioned in this space before that sitting in church can be a trying experience for us. We never know when a song, a prayer, or a statement made in Sunday School banter might open the floodgates of sadness that reside within us from losing Ethan. Of course, this is also true in everyday encounters, but we have found that the likelihood of it occurring is magnified in church because mortality and miracles are topics of discussion in church much more often than in everyday life.