Ethan’s Mom: “What is some of the deepest suffering you have experienced, and how did you cope through it?”

Those words have been staring me down this week. The question is number 4 in this week’s BSF lesson, entitled “Perseverance in Suffering.” There is about an inch of white space underneath in which to write an answer. Who among us can describe their suffering and coping strategies in that much room?

After five days of sitting down to work on my lesson only to walk away after a few minutes of staring at it, I have finally come up with an answer:

“See blog.”

Since the inception of this blog, it has been a safe place to process our thoughts about suffering, grief, and loss. The loss of Ethan, primarily, but also the myriad of secondary losses we experience as a result. I don’t know that anyone out there reads this consistently or anticipates hearing from us, but that’s OK. We have viewed the blog first and foremost as an outlet for us. It is a blessing, but not necessarily a goal, for others to benefit from our writings.

All that to say, I’m not sure anyone has been sitting around thinking, “I wonder why Ethan’s parents don’t post as often as they used to?” But in case you have, it is not because our hearts have healed. That is one thing I don’t like about the wording of the above question – it is in the past tense. How did you cope through it? I cannot be the only one who would rather it use the present participle – how are you coping through it?

I last held Ethan in my arms in the early hours of March 10, 2017. If Jesus tarries, as the old Baptist preachers say, I will live the rest of my days longing to hold him again. There is no earthly end to this suffering.

Of course, daily life does not look the same as it did this time seven years ago, coming up on the first anniversary of March 10th, for many reasons. Seven years ago, I had to make an intentional effort to enter into joy, and even then it was for brief moments at a time. Grief was a constant companion, always right in front of my eyes no matter what else I tried to look upon. But life didn’t stop – specifically, the needs of my four living children continued. We had help from friends and family, but I needed to care for them as much as they needed to be cared for by their mother. In many ways, they were my gateway to the moments of joy my soul so desperately needed. Jumping on the trampoline, making muffins, zoo outings, giving and receiving warm hugs – these were the means of grace that “brought my soul up from Sheol” and “restored me to life” (Psalm 30:3).

Now, at times, I have to make an intentional effort to enter into sadness. While the kids still bring me much joy, we have moved into a season where their schedules dictate my schedule in a new way. Instead of falling into place around a naptime, my day now centers around school and extracurricular activities. Taking care of the four living kids seems more urgent than giving myself space to grieve. Having a “sad day” here and there was a necessity then, but it seems like a luxury now. Sometimes, it is easier to skirt around the edges as opposed to diving into the deep. We have written on the blog about how difficult and costly it can be to sit with others in their darkest moments. In some ways, I feel like it is also costly to sit with myself.

I just can’t dash off a quick answer to the question in my BSF lesson in a few sentences or write an entire blog post in the carpool line. Writing these posts requires quiet, time, and space to think – all things at a premium at this stage in the game. I just counted, and I have 8 unfinished entries on my Google Drive. The phrase, “I should write a blog post about that…” rolls through my consciousness with regularity, but when I looked at the last few entries on the blog, I realized there wasn’t a single post between Ethan’s 7th birthday and his 8th birthday. That breaks my heart a little.

Speaking of his birthday, this year it fell on the first day back to school after winter break. There aren’t many quiet moments for reflection in between making the magic of Christmas happen and cleaning up the aftermath. Then Saturday before school started, we celebrated #4’s birthday with a party at a local rock climbing gym. He deserves to celebrate with his friends, and I want to be able to give him that experience. The only way that happens, though, is if I can compartmentalize my feelings about hosting a birthday party for him where none of the guests know he has a twin brother who should be here as well.

Although I felt a little bad for thinking this, I was glad that I would have some quiet time while they were at school on the 7th. I knew I needed to feel my feelings, but when the day arrived, I felt numb. The temperatures were just above freezing, limiting our visit to his grave. The house was in need of a thorough cleaning after two and a half weeks of everyone being home full time, and I couldn’t shake the compulsion to scrub all the bathrooms. Then after school we ate birthday cake before all the regularly scheduled activities. The day passed in a blur, and I hardly shed a tear.

At my next monthly session, I related to my counselor how not crying on Ethan’s birthday really bothered me. She put words to my feelings. “You haven’t had a chance to enter in,” she said. I am not used to thinking of grief that way. For years, it crashed in like a tidal wave. It still does at times. A birth announcement, a conversation about the challenges of raising twins, an icy forecast – all of these and many more can bring strong waves of grief that knock me off balance a little, or a lot, depending on the exact circumstances. The waves still come relentlessly, but not every wave knocks me down.

I guess the world might look at this and call it healing, or closure. I don’t think that’s quite it though. I do need to enter into the darkness at times – if I try to ignore it through staying busy or just waiting until the “right time” comes, things do not go well for me and for those around me. But I am not at the mercy of the darkness in the same way, either. A sneaky voice whispers in the back of my mind: “Is this leaning too far into joy? Am I leaving Ethan in the past?”

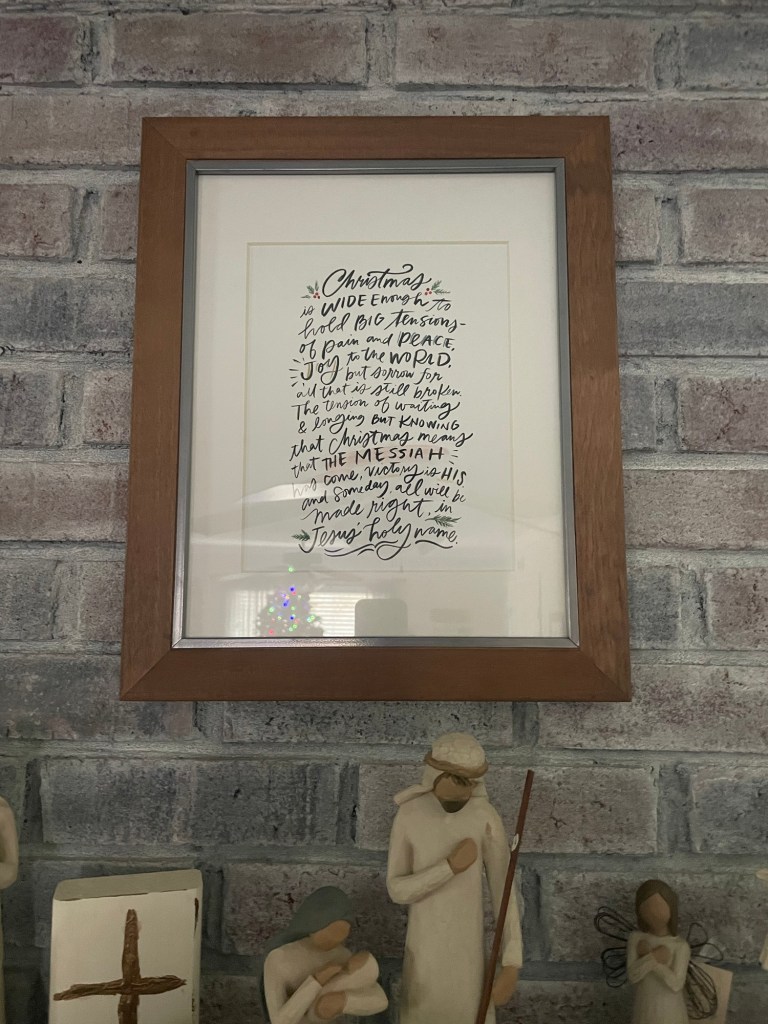

Love is eternal; pain is not. One day, pain will be no more. That is the real point of this week’s BSF lesson, but I had a hard time seeing that through all the attempts to rationalize and spiritualize our response to suffering. As we move ever closer to the day when we see Ethan again, it is right to feel the balance tipping in favor of joy. It is also right to fully enter into the sorrow. Both are necessary; both are, in their own ways, good. In the words of A Liturgy for Embracing Both Joy & Sorrow, “For joy that denies sorrow is neither hard-won, nor true, nor eternal. It is not real joy at all. And sorrow that refuses to make space for the return of joy and hope, in the end becomes nothing more than a temple for the worship of my own woundedness.” It goes on to remind us that we have a role model in our practice of holding the tension:

Maybe that is where the confusion lies for some who hear our story. People assume we are angry at God and need to work through those feelings to arrive at a place where we can continue to believe and to worship Him. They think that to embrace joy necessitates leaving lament behind. They presume that finding peace and purpose in our suffering requires that we wholeheartedly accept God’s sovereignty and abandon our unanswered questions. But it’s both/and, not either/or. We are at liberty to lament and rejoice. I don’t know if anyone else needed to hear that – I sure did.

Anywhere

By: The Gray Havens

Eyes wide late night windowsill open

There’s a shadow at my back saying everything’s broken

So I pointed to a star saying that’s where I’m going

Second to the right then straight til’ morning

Praying in the dark please if you’ve got a moment

There’s a shadow in my mind says you’re never gonna notice

That I been dying inside I been trying not to show it

But I never want to feel this way again

So take me anywhere anywhere anywhere but here

Ah take me anywhere anywhere anywhere but here

I don’t care I don’t care I don’t care where

Just take me anywhere

Anywhere but here

I’ve been trying to keep the faith

I’ve been trying to trust the process

But it just feels like pain, doesn’t feel like progress

And it seems like a waste if I’m really being honest

I’ve been trying to fly away but I keep falling

And Neverland keeps calling

So take me anywhere anywhere anywhere but here

Ah take me anywhere anywhere anywhere but here

I don’t care I don’t care I don’t care where

Just take me anywhere

Anywhere but here

I could spend my nights

Staring at the sky

Dream of ways to fly away

Chasing happy thoughts

Or a better plot

While I lose another day

And what a tragedy

To awake and see

That I’ve never learned to stay

So bring me to a place

Where I don’t chase escape

Somewhere I could finally say

Don’t take me anywhere anywhere anywhere but here

Don’t take me anywhere anywhere anywhere but here

Don’t take me anywhere anywhere anywhere but here

Don’t take me anywhere, anywhere

Eyes wide late night windowsill open